So far we have discussed digital audio signals as if they were capable of

describing any function of time, in the sense that knowing the values the

function takes on the integers should somehow determine the values it takes

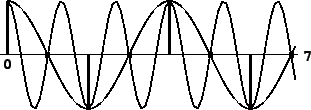

between them. This isn't really true. For instance, suppose some function

![]() (defined for real numbers) happens to attain the value 1 at all integers:

(defined for real numbers) happens to attain the value 1 at all integers:

It is customary at this point in discussions of computer music to invoke

the famous

Nyquist theorem.

This states (roughly speaking) that if a function is a finite or even infinite

combination of sinusoids, none of whose angular frequencies exceeds ![]() ,

then, theoretically at least, it is fully determined by the function's values

on the integers. One possible way of reconstructing the function would be

as a limit of higher- and higher-order polynomial interpolation.

,

then, theoretically at least, it is fully determined by the function's values

on the integers. One possible way of reconstructing the function would be

as a limit of higher- and higher-order polynomial interpolation.

The angular frequency ![]() , called the Nyquist frequency, corresponds

to

, called the Nyquist frequency, corresponds

to ![]() cycles per second if

cycles per second if ![]() is the sample rate. The corresponding period

is two samples. The Nyquist frequency is the best we can do in the sense that

any real sinusoid of higher frequency is equal, at the integers, to one whose

frequency is lower than the Nyquist, and it is this lower frequency that will

get reconstructed by the ideal interpolation process. For instance, a

sinusoid with angular frequency between

is the sample rate. The corresponding period

is two samples. The Nyquist frequency is the best we can do in the sense that

any real sinusoid of higher frequency is equal, at the integers, to one whose

frequency is lower than the Nyquist, and it is this lower frequency that will

get reconstructed by the ideal interpolation process. For instance, a

sinusoid with angular frequency between ![]() and

and ![]() , say

, say ![]() ,

can be written as

,

can be written as

|

We conclude that when, for instance, we're computing values of a

Fourier series (Page ![[*]](crossref.png) ),

either as a wavetable or as a real-time signal, we had better leave out any

sinusoid

in the sum whose frequency exceeds

),

either as a wavetable or as a real-time signal, we had better leave out any

sinusoid

in the sum whose frequency exceeds ![]() . But the picture in general is not

this simple, since most techniques other than additive synthesis don't lead to

neat, band-limited signals (ones whose components stop at some limited

frequency). For example, a sawtooth wave of frequency

. But the picture in general is not

this simple, since most techniques other than additive synthesis don't lead to

neat, band-limited signals (ones whose components stop at some limited

frequency). For example, a sawtooth wave of frequency ![]() , of the form

put out by Pd's phasor~ object but considered as a continuous

function

, of the form

put out by Pd's phasor~ object but considered as a continuous

function ![]() , expands to:

, expands to:

Many synthesis techniques, even if not strictly band-limited, give partials

which may be made to drop off more rapidly than ![]() as in the sawtooth

example, and are thus more forgiving to work with digitally. In any case,

it is always a good idea to keep the possibility of foldover in mind, and

to train your ears to recognize it.

as in the sawtooth

example, and are thus more forgiving to work with digitally. In any case,

it is always a good idea to keep the possibility of foldover in mind, and

to train your ears to recognize it.

The first line of defense against foldover is simply to use high sample rates; it is a good practice to systematically use the highest sample rate that your computer can easily handle. The highest practical rate will vary according to whether you are working in real time or not, CPU time and memory constraints, and/or input and output hardware, and sometimes even software-imposed limitations.

A very non-technical treatment of sampling theory is given in [Bal03]. More detail can be found in [Mat69, pp. 1-30].